关于克拉克探险队与《穿越陕甘》

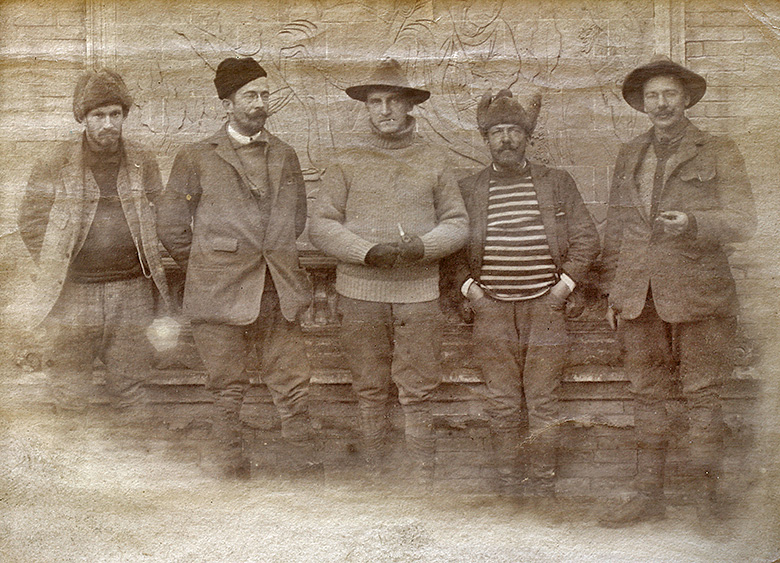

Members of the expedition, from left to right:

A. de C. Sowerby, R. S. Clark, Nathaniel H. Cobb, G. A. Grant, H. E. M. Douglas.

Yulin Fu, November, 1908. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image #2008-3140

Yulin Fu, November, 1908. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Image #2008-3140

克拉克探险队与《穿越陕甘》

撰文:李炬 图片:李炬/克拉克艺术中心

Born on June 25, 1877 in New York, Robert Sterling Clark was heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune of his grandfather, Edward. In 1899 he graduated from Yale University with a degree in engineering. Joining the 9th Infantry of the U.S. Army, he served in the Philippines, and in 1900, at the Battle of Tianjin; he was stationed with the U.S. Legation Guard in Beijing through 1905. Later that year he retired from military service and returned to the United States.

Clark must have become fascinated with the history and culture of the ancient empire after this first glimpse of China. Perhaps noticing the lack of detailed knowledge about the terrain and natural life inhabiting the Loess Plateau of northwest China, he decided to organize and conduct a detailed scientific expedition to the region.

Clark spent several years meticulously planning the expedition. The route traversed the areas of Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia and there were plans to return to the coast via Sichuan Province and the Yangtze River. He engaged a talented, international cadre of officers for the expedition: Nathaniel Cobb, an American artist①; Hazrat Ali, a cartographer of the Survey of India; Captain H. E. M. Douglas from The Royal Army Medical Corps as the surgeon and meteorologist; and Arthur de Carle Sowerby, a British naturalist who was born in China, to study the botany, biology, and geology of the region.

In 1908, Clark’s team embarked from Taiyuan on their eighteen-month journey. In 1912, Through Shên-Kan: The Account of the Clark Expedition in North China 1908-9, written by Clark and Sowerby, was published in London. Clark was personally involved in the scientific exploration, measurement, and recording of detailed data during the journey, authorship of the final reports, and the publication itself. He kept the expedition’s gear and most of the field notes for the rest his life, ultimately donating these artifacts and records to the museum he founded with his wife, Francine, in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Among these records are the notebooks registering the latitude and longitude data — measurements which have proven remarkably accurate against today’s state-of-the-art technology.

It is worth noting that the Clark expedition was conducted during a time when some western explorers carried off China’s cultural relics as a matter of course. The Clark expedition was an exception to this rule: it was, in contrast, concerned solely with observing the region, its people, and its heritage. High-minded in its intentions, the expedition balanced its interests in scientific inquiry with a genuine curiosity for the social, political, and cultural history of the regions it traversed, recording these humanistic findings in photographs and diary entries.

The Clark expedition was distinctive for its lack of adherence to the general trends of Western explorations of the time. Since the Second Opium War, particularly at the end of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, western China, Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet and other border areas became attractive to foreign adventurers. It was the period when the great world powers, using their spheres of influence, infringed upon China’s sovereignty. The many “study tours” conducted by Western explorers, regardless of the parties concerned, were consciously or unconsciously to a certain extent all tinted with strong imperialist and colonial instincts. For example, the Russians were keen to examine Xinjiang and Mongolia; the French focused on Guangxi and Yunnan; the British showed a special interest in Tibet and the Japanese sent a number of geologists to the northeast of China to search for mineral deposits. Foreign collectors of cultural artifacts, aware of treasures such as the Dunhuang Grotto Murals, waited for their opportunity.

Standing aloof of these national interests was the Clark expedition. I find the following characteristics of the Clark expedition to be significantly different from most others of its day:

1. Unlike other expeditions with their ulterior motives, the motivation of the Clark expedition was very simple: scientific exploration of the hinterland of the Loess Plateau. The region was relatively untouched — there were no predecessor expeditions which had set foot there. The topics of the expedition’s research — geography, geology, meteorology, biology, and ethnography — distinguish it from others focused solely on obtaining resources or artifacts.

2. It was financed by Clark personally, as a private sponsor not representing any sovereign power.

3. Clark’s was an international team, not representing any commercial or political interest. He was an American; Sowerby a Chinese-born Englishman; the remainder of the team included Britons, Americans, and Indians.

4. The expedition was approved by the Qing government. Customs declarations were made on equipment such as weaponry, local officials were informed before entering different areas, and fees were paid for the leased telegraph line used for mapping communication.

5. The expedition treated and gave medical attention to local inhabitants freely and as a matter of course. According to the book Through Shên-Kan: The locals often came to the camp to seek help, usually they were treated with conventional drugs, if someone was injured, he could obtain care … the news of a doctor in our expedition spread like wildfire, people came to our camp to ask for treatment and medicine. They all received help to the best of our abilities. Villagers were so grateful for every single pill we gave to them.

After the expedition ended in 1909, Clark continued to concern himself with the situation in China while living in Paris and New York. Letters from the 1910s and 1920s reflect how he wished to revisit with Francine, whom he met shortly after settling in Paris in 1910. However, the political turmoil of the times — in China and in Europe — prevented his return. Nevertheless he supported Sowerby’s continued scientific study throughout China and also funded Sowerby’s magazine, The China Journal (published in Shanghai), which helped introduce Chinese culture, arts, science, and history to the West. Clark also collected and read many books on China, including Pearl Buck’s novels about the country.

Apart from the enthusiasm he displayed for the expedition, Clark had two major life pursuits: collecting art and horse racing, achieving great success in both these areas.

On May 17, 1955, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute opened in Williamstown, Massachusetts, offering the first public display of the Clarks’ art collections in a setting they personally planned and built. On December 29, 1956, Sterling Clark died at the age of 79. His remains and those of Francine were buried among the flower beds between the steps at the original entrance of the Clark.

In 2010, with great emotion, I paid tribute to the memory of the Clarks when I visited their resting place. Respecting and admiring a noble character and his spirit of exploration, one hundred years after he left China, I felt proud to be a Chinese successor to his interest. I, too, feel as though I have followed in his footsteps and explored a land which is unknown to many.